The deaths at sea of a mother and child have further exposed the flaws in a pact between Italy and Libya that has led to thousands of migrants being forcibly returned to the chaotic north African country.

Their bodies were found last week in the drifting wreckage of a boat off the Libyan coast by rescuers from the Spanish ship, Proactiva Open Arms. A woman from Cameroon was also found clinging to a piece of wood.

Sharing harrowing images of the bodies and the terrified survivor, the NGO accused the Libyan coastguard of abandoning the trio after they refused to be taken back to Libya, the main point of departure for migrants attempting the perilous crossing to Europe, with the rest of the intercepted group.

Libya’s coastguard has been patrolling the Mediterranean sea since striking a deal with Italy in February 2017 that empowered it to bring migrants back to a country where aid agencies say they suffertorture and abuse. The deal, which entailed Italy providing funds and equipment, was made by Marco Minniti, the former interior minister from the centre-left Democratic party, in an attempt to stem the migrant flow.

The agreement was recently reinforced by Italy’s new far-right interior minister, Matteo Salvini, who travelled to Tripoli in June “to help Libya as well as Italy block migration”.

“The Italy deal is really unconscionable at a time when the world needs leadership and compassion,” Iverna McGowan, the director of Amnesty International’s European institutions office, told the Guardian.

“To blindly sign a deal like that and close your eyes to the human consequences is very chilling.”

In January 2017, the EU unveiled a €200m plan aimed at stopping migration from Libya, including €32m to expand its training programme for the Libyan coastguard.

The simultaneous plans have proved successful at reducing migration: the number of migrants landing on Italy’s southern shores in the first half of 2018 was down 81% on the same period last year.

As politicians celebrated, testimony recounted to the Guardian by migrants who have arrived in Sicily in recent months reflected the human implications of an agreement that has caused death, severe suffering and torn families apart.

“Libya is the worst place on earth,” said Ibrahim Diallo, a 20-year-old man from Gambia. “If you are a black African they automatically consider you a slave.”

Quick GuideWhy is Libya in chaos?

Show

What happened after the Libyan revolution?

Muammar Gaddafi was ousted as president in 2011 after more than 40 years in power. But deep division between his supporters and adversaries persisted. An internationally recognised National Transitional Council took over, but quickly succumbed to schism, particularly between east and west.

How did things get so chaotic?

The transitional authorities found it impossible to extend their writ across the whole country, which was splintering into myriad factions: former regime loyalists, revolutionary brigades, local militia, Islamists, old army units, tribes, people trafficking gangs.

What about elections?

A General National Congress was elected in 2012 and established itself in Tripoli. But when a national parliament was elected in 2014, the GNC refused to accept the result; the new body had to install itself in the eastern city of Tobruk. Libya now effectively had two governments - the former buttressed by Islamist militias in its Tripoli stronghold, the latter supported by Khalifa Haftar, a renegade army colonel now head of the armed forces.

What about the international community?

Libya has become too unsafe for diplomats and most aid workers. The UN pulled its staff out in 2014 and foreign embassies followed suit. Tripoli international airport is largely destroyed by fighting.

Where has this left Libya?

The conflict has killed 5,000, ruined the economy, driven half a million from their homes and trapped hundreds of thousands of migrants seeking to get north to Europe in a nightmarish network of brutal camps. Diplomatic attempts at reconciliation have proven fruitless thus far.

Diallo was detained in a camp where he was forced to work and clean the streets at gunpoint. “I saw Africans getting shot in the legs just because [the armed gangs] wanted to check if their weapons worked.”

A migrant from Nigeria, who asked not to be named, said he suffered serious burns after being set on fire by his captors for failing to raise ransom money. He had been in a detention camp for two years, where he recalled often “waking up with a dead man next to me”.

Chica Kamara, from Sierra Leone, has had no news of his son since the pair got separated at sea and the 10-year-old boy was taken back to Libya.

“We left Sierra Leone because of war, Ebola and dictatorship,” said Kamara, who had fallen into the sea when the Libyan coastguard intercepted a boat with his son on board. “I wanted a better life for my son. When I realised he was being taken away I started to scream and cry.”

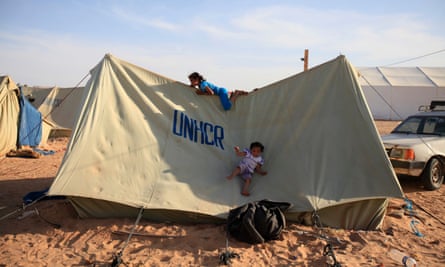

Women tell of being repeatedly raped in Libya, where the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) estimates there are 662,000 migrants. The number of people detained in appalling conditions in official camps has almost doubled to 9,300 within the last three months, the UN agency said earlier this week, although that doesn’t include the many held in camps run by warlords or people smugglers. Within the first five months of 2018, more than 40% of migrants who left Libya were sent back.

Carlo Parini, a chief inspector in the Sicilian port of Syracuse, said his team gathered as much information as possible from migrants. “It’s hard to hear their stories,” he added. “Especially when you have pregnant women telling you they have been beaten or tortured.”

An official at the Italian ministry of interior saidthe country was forced to make the deal with its former colony after several pleas to the EU to share the migrant burden failed to yield a response. “Our main contribution is supplying boats and equipment to the Libyan coastguard,” he said. “In June last year, some 18,000 people landed in a week, and the EU did nothing to help.”

But the agreement is also a consequence of the EU’s Dublin regulation, which allows member states to send migrants back to the EU country they arrived in, usually Italy or Greece. In 2016, almost 35,000 people were returned to Italy from other EU states, predominantly France.

“At the same time, southern Italy was also dealing with thousands of arrivals from Libya,” said Fulvio Vassallo, an asylum law professor at the University of Palermo. “On top of this, countries in Europe rejected [a plan] to relocate migrants.”

By being complicit in returning people to countries where they could be subjected to torture, the EU is violating international law, say experts. In March, the Proactiva Open Arms ship was seized by Sicilian authorities and three of its crew accused of facilitating illegal immigration for refusing to hand over migrants to Libya. Upon releasing the vessel in April, a judge recognised that Libya was not a safe place and that the migrants could not have been taken back.

A looming election campaign dominated by immigration also encouraged Minniti to collaborate with Libya, although the Democratic party was eventually ousted in the ballot in early March. Italy’s new populist administration has since used virulent tactics to fulfil its anti-immigration pledge, including denying docking rights to rescue ships, while trying to push an inharmonious EU into sharing responsibility. However, a proposal by Italy to create reception and identification centres in Africa received a blow on Friday when it was rejected by Libya.

But as the EU battles, traffickers continue to make all the gains out of migrant suffering.

“Traffickers are having an easy life,” said Alfonso Giordano, a politics professor at Luiss University in Rome. “If we don’t resolve this in a shared, structured way over the long-term, there’ll continue to be massive problems and countries like Libya will continue to use blackmail.”